Greener pastures: Canadian agriculture a bright spot for trade

Check out this report highlighting Canadian agriculture trade and investment trends

Check out this report highlighting Canadian agriculture trade and investment trends

Agriculture is a significant contributor to the Canadian economy, accounting for 11% of exports and 2.3 million jobs. This report provides an overview of this sector’s major products, trade performance, investment patterns and export opportunities.

Agriculture accounts for about 7% of Canadian economic output, 11% of exports, 8% of imports and 2.3 million full-time equivalent jobs (12% of the total) when including related industries like manufacturing, and services such as distribution and finance. Agricultural exports have grown at three times the rate of overall Canadian exports between 2008 and 2017. Therefore, in terms of contribution to GDP, employment and trade, this sector is significant.

Canada is one of the world’s largest food producers, particularly in vegetable products, like wheat and pulses. Canada’s agricultural trade is also closely integrated with North American supply chains, as reflected in trade flows of live animals and animal products.

This report discusses Canada’s trade performance, investment patterns and export opportunities. The first section addresses trade performance in four broad categories of agricultural trade:

The first three are typically considered “primary” sector agriculture, while the last one is a subset of manufacturing or “secondary” sector industrial activity.

The report then moves on to review investment patterns in these activities. This includes investment into Canada, as well as Canadian investment abroad. The report concludes with areas of opportunity for niche products, including organics.i

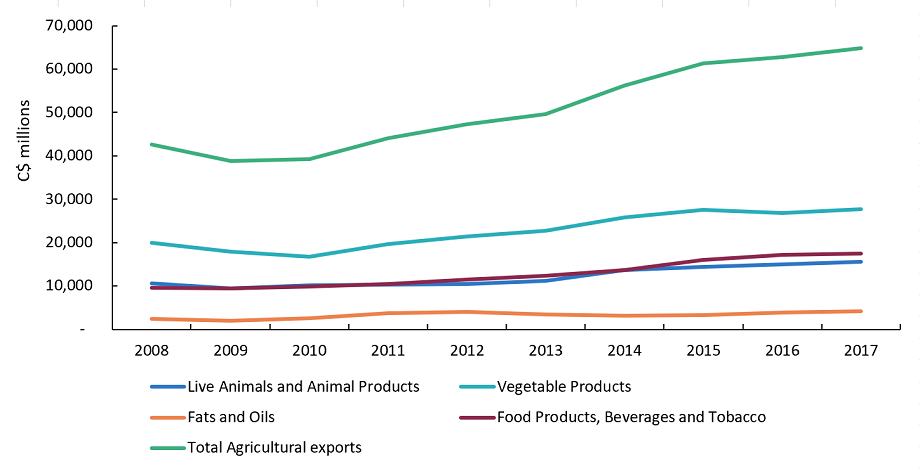

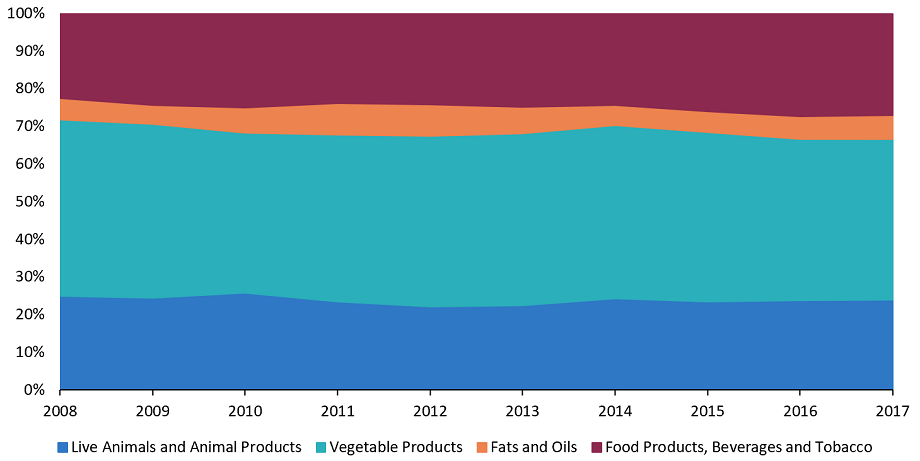

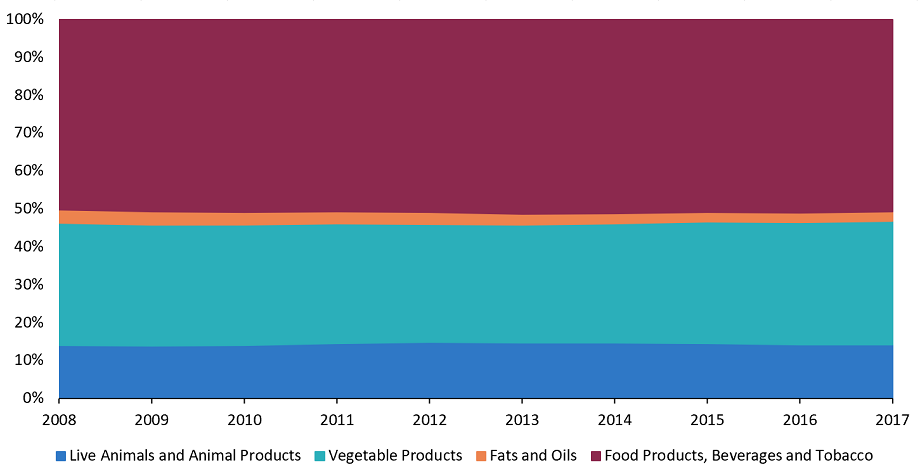

From 2008 to 2017, Canada’s agricultural exports increased at a compound average annual growth rate (CAGR) of nearly 5% (nominal basis), peaking at $65 billion in 2017 (Figure 1). The largest segment on average during this period was vegetable products (44%), followed by food products, beverages and tobacco (25%), live animals and animal products (24%), and then fats and oils (7%) (Figure 2).

The largest share of exports has consistently been vegetable products, reaching nearly $28 billion in 2017 (43% of total). However, this segment’s CAGR was the lowest for 2008 to 2017 at less than 4%. Therefore, this segment has shown growth, but growth has been slower than in the other three segments.

Food products, beverages and tobacco are the second leading export segment, reaching $17.5 billion in 2017. Encouragingly, this segment had the highest CAGR for 2008 to 2017 at 7%. This is helpful to the Canadian economy because these processing activities make a large contribution to GDP (value added). As these goods are intermediate or finished, their sales prices are higher, more people are employed in processing and distribution, and their industrial production requires purchases of other goods and services from Canadian suppliers (such as machinery and equipment, specialized data and information services).

Live animals and animal products remain an important segment, with exports exceeding $15 billion in 2017. Much of this is tied to supply chains in the North American meat-processing industry.

Fats and oils showed 6% CAGR from 2008 to 2017, but remains relatively small as a segment, accounting for about $4 billion in agricultural exports in 2017.

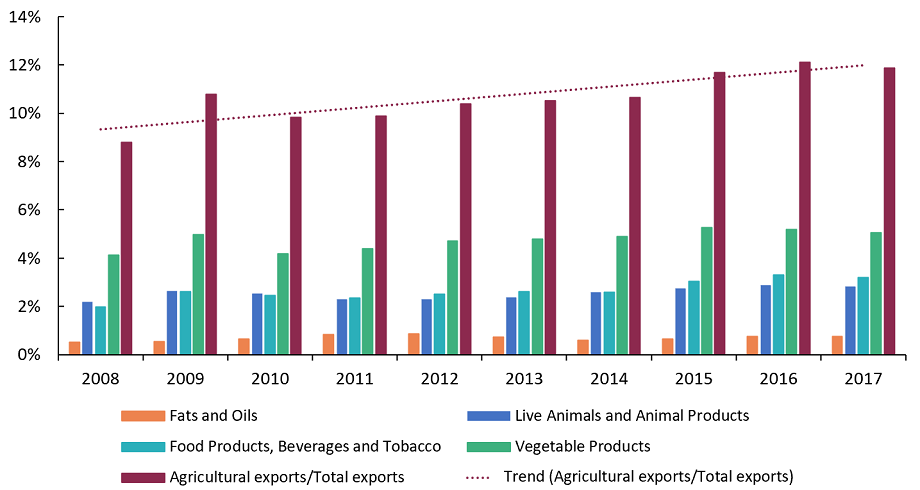

All together, the above exports accounted for an average 11% of total Canadian exports. The trend has been positive, as reflected in the 12% share from 2015 to 2017 as compared with 9% in 2008 and 10% to 11% from 2009 to 2014 (Figure 3).

Moreover, given Canada’s total export growth of only 1.4% CAGR from 2008 to 2017, agricultural exports and their nearly 5% CAGR constitute a bright spot as an export performer. This translates into a $22-billion difference in agricultural exports in 2017 as compared with 2008, and a dollar value that is 1.5 times 2008 values.

Official full-year 2018 data for agricultural exports hadn’t been released by the time of writing. Nonetheless, data was available through the third quarter of 2018. Based on these data, EDC estimated that agri-food exports would approximate $64 billion in 2018, a decline of 0.5% from 2017. Declines were expected in food and beverage products, seafood and live animals, while growth was expected in grains and oilseeds and all other agriculture products. Such predictions may have been optimistic in light of recent trade challenges with China, which has reduced its imports of Canadian canola.

EDC’s forecast for 2019 expects a rebound in agricultural exports to $66 billion, representing growth of nearly 4%. However, such predictions are subject to revision should trade challenges persist with China and if exporters are unable to find substitute markets to replace these losses. Export growth is expected in all categories except live animals, subject to the caveat above which would limit growth in the oilseed sector.

As for trade diversification, there’s mixed evidence, notwithstanding growing concentration of export sales at the top. In 2008, Canada’s leading export markets were the U.S. (53%), Japan (9%), China (4%) and Mexico (4%). In 2017, U.S. market share retained its large lead (54%), China (12%) overtook second place from Japan (7%), while Mexico remained fourth (3%). Therefore, in 2017, 76% of Canadian agricultural exports went to these four markets, as compared with 70% in 2008. This indicates increasing market concentration of Canadian agriculture exports. As well, a smaller share of exports went to markets outside the top 10 countries, falling from 22% in 2008 to 17%.

More positively in terms of trade diversification, the dollar value of Canadian agricultural exports to countries outside the Top 10 have increased about 2% per year. In 2017, these exports were $11 billion, up from $9.5 billion in 2008. Moreover, five of the Top 10 export markets weren’t on the Top 10 list in 2008, suggesting that Canadian exporters have been able to cultivate new markets.

As for growth rates, the biggest change was with China. Agricultural exports to China increased from nearly $2 billion in 2008 to nearly $8 billion in 2017. Including Hong Kong would raise agricultural exports to this market in 2017 to about $8.5 billion. While these figures are small compared with Canadian agricultural exports to the U.S. ($35 billion in 2017), they constitute a very high growth rate. As noted above, these figures are subject to potential decline due to current trade challenges, although they’re expected to remain well above 2008 levels. By contrast, growth in agricultural exports to Japan (2%) and Mexico (3%) were tiny compared with the year-on-year average growth rates to China of 41%.

Apart from these four leading markets, only Indonesia has remained among the Top 10 for Canada. In 2017, India, United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong, South Korea and Vietnam were among the Top 10, although together they accounted for only 6% of total ($4 billion). In 2008, Belgium, Algeria, Iran, the U.K. and Russia were among the leaders, buying $3 billion in agricultural goods from Canada, at the time 7% of total.

With the global population expected to reach nine billion by 2050, agri-food is poised for rapid growth. Check out our free trade talk and explore the opportunities.

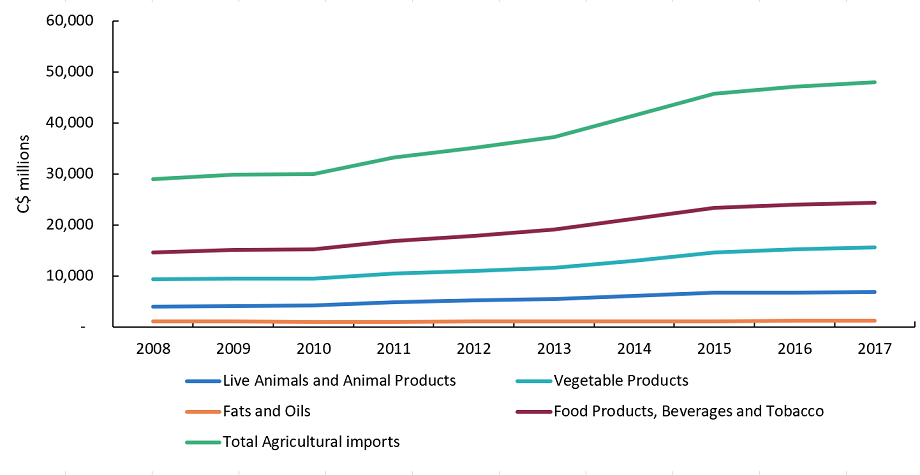

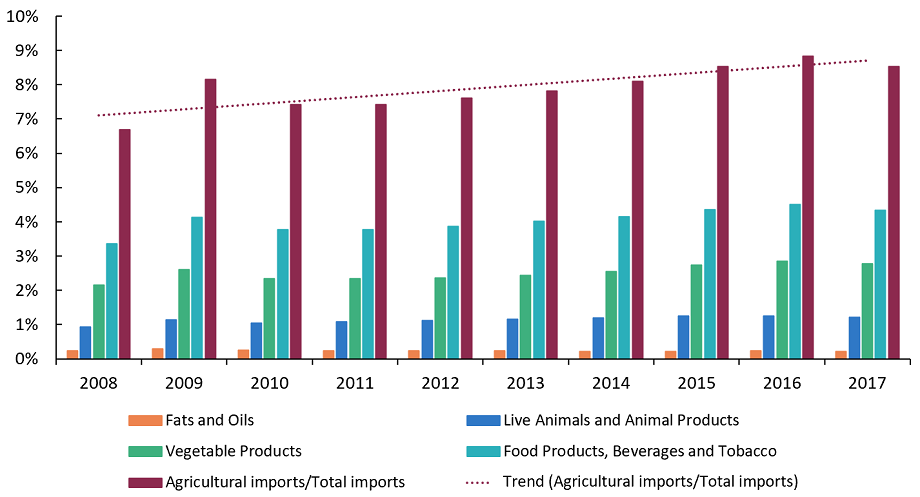

From 2008 to 2017, Canada’s agricultural imports increased at a CAGR of nearly 6%, slightly higher than agricultural exports. Agricultural imports peaked at $48 billion in 2017 (Figure 4). The largest segment during this period was food products, beverages and tobacco (51%), followed by vegetable products (32%), live animals and animal products (14%), and fats and oils (3%) (Figure 5). In all four categories, shares of total agricultural imports were steady from 2008 to 2017.

The largest share of agricultural imports has consistently been food products, beverages and tobacco vegetable products, reaching $24 billion in 2017 (51% of total). As high value-added products, these are also the most expensive for consumers. The CAGR was 6% for 2008 to 2017, therefore, consistent with the broad agricultural import growth trend, and comparable to the other two largest import segments.

Vegetable products were the second-leading import segment, reaching $16 billion in 2017. Live animals and animal products were the third-leading import segment, with imports at $7 billion in 2017.

Only fats and oils showed little share and growth. Imports in 2017 were just above $1 billion, and little changed from 2008. The CAGR from 2008 to 2017 was less than 2%, well below the other three segments’ 6% growth rate.

All together, the above imports accounted for an average 8% of total Canadian imports. The trend has been one of moderate growth, as the total share of imports was 7% in 2008. More recently, the share has increased to above 8% since 2014. These rates are all much higher than the 3% CAGR for total Canadian imports from 2008 to 2017. However, in general, the share of agricultural imports has been flat since 2008 (Figure 6).

Import market sources have been very stable since 2008. Of the Top 10 leading import markets in 2017, nine were among the top performers in 2008. India made it into the Top 10, unlike in 2008, when the U.K. was No. 10 (now 11th).

The list and the country rankings are little changed in recent years. The top six suppliers in 2008 were also the top six in 2017. These were the U.S., Mexico, China, Italy, France and Brazil. Thailand and Chile swapped positions as the seventh and eighth largest suppliers between 2008 and 2017 with little difference in import value in 2017. India is now in the top 10, unlike in 2008, while Australia remains No. 10.

In addition to the list and order, the relative shares have shown little change. The U.S. is still by far the largest source of agricultural imports at 59% in 2008 and 57% in 2017. The downward shift from the U.S. appears to have been captured by Mexico, which increased from 3% to 6%. Therefore, trade diversification appears to have been more of a reconfiguration of NAFTA shares, rather than a breakthrough in Canadian efforts to reduce concentrated exposure with U.S. or regional markets.

Other more distant sources from Europe, Asia and Latin America still account for 16% of total agricultural imports among the Top 10. Additional sources outside the Top 10 accounted for 22% of total in 2017, as opposed to 20% in 2008.

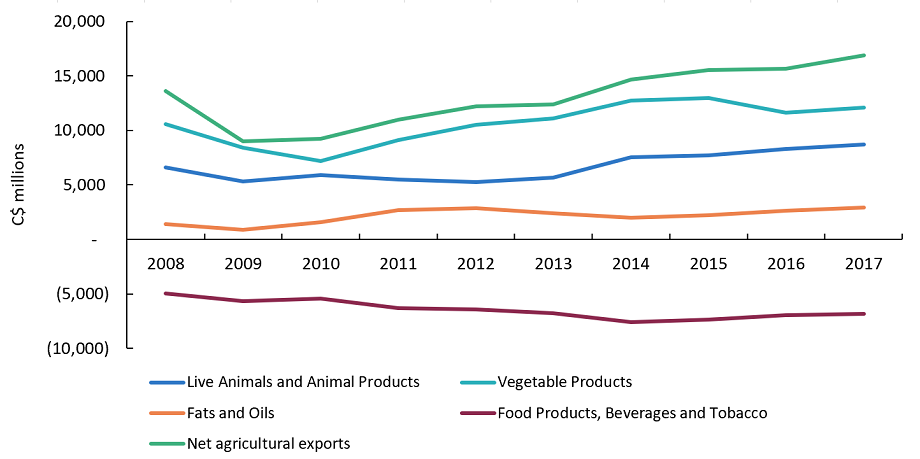

Based on the above figures, Canada has increased its net trade in agricultural goods since 2008. Total agricultural exports less agricultural imports were $17 billion in 2017, as compared with a low of $9 billion in 2009 (Figure 7). The CAGR overall has been 2.4% since 2008.

The net was nearly $14 billion in 2008 before the global financial crisis affected these markets. Since then, Canadian exporters have clawed their way back to increase net positions, and net exports have exceeded 2008 levels since 2014.

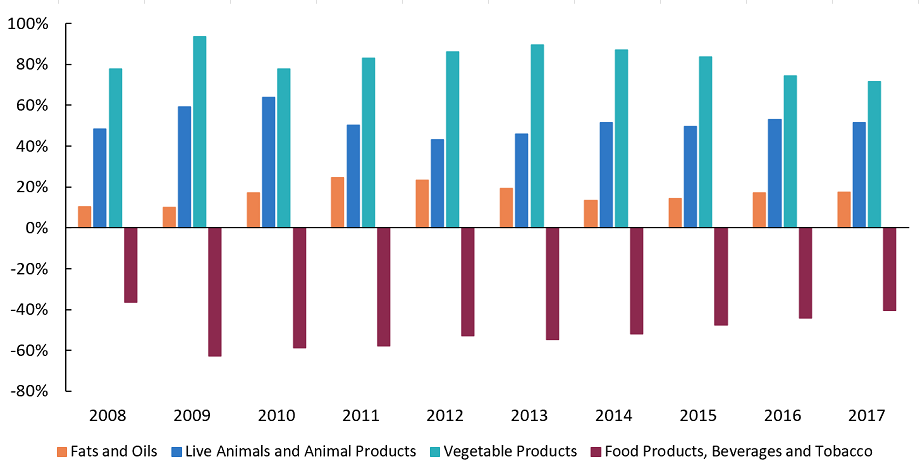

Trade trends have been favourable for Canadian exporters in vegetable products, live animals and animal products, and oils and fats. Together, these three segments generated a net trade surplus of $23.5 billion 2017, more than half in vegetable products. However, Canada consistently incurs deficits in the higher value-adding activities associated with food products, beverages and tobacco products.

This is partly due to the comparatively low levels of inward investment in food processing, which have limited Canadian food manufacturers’ ability to capture a greater share of the cross-border and international market for higher value processed foods and beverages. The trade deficit in this segment was nearly $7 billion in 2017.

It’s unclear how current trends will impact future efforts to diversify markets and increase surpluses. On a product basis, vegetable products have generated the largest surpluses over the years. However, these have levelled off since 2014, and their CAGR of 1.5% is the lowest of the three surplus segments. Live animals and animal products show higher CAGR of 3%, but values are still about two-thirds of vegetables products, so little changed in the mix. The highest CAGRs (nearly 9%) are in fats and oils, but these are small in value.

Meanwhile, in the food products, beverages and tobacco segment, the net deficit has shown several years of shrinkage in value after peaking at nearly $8 billion in 2014. Therefore, while vegetable products show sluggish growth at best on the surplus side, the net deficit in food products, beverages and tobacco is also declining, offsetting trends in vegetable products (Figure 8).

In summary, the trends are largely favourable for Canada. Agricultural exports exceed agricultural imports, generating consistent trade surpluses at a 2.4% CAGR from 2008 to 2017. This contrasts with Canada’s overall figures, which show deficits of $15 billion in 2017, nearly three times deficits in 2009. Since 2008, Canada has had only three years in which exports exceeded imports, much of this linked to commodity prices and demand overseas for raw materials and energy products. Therefore, given the considerable market risks associated with such dependencies, the current account in agricultural products is a positive performer for the Canadian economy.

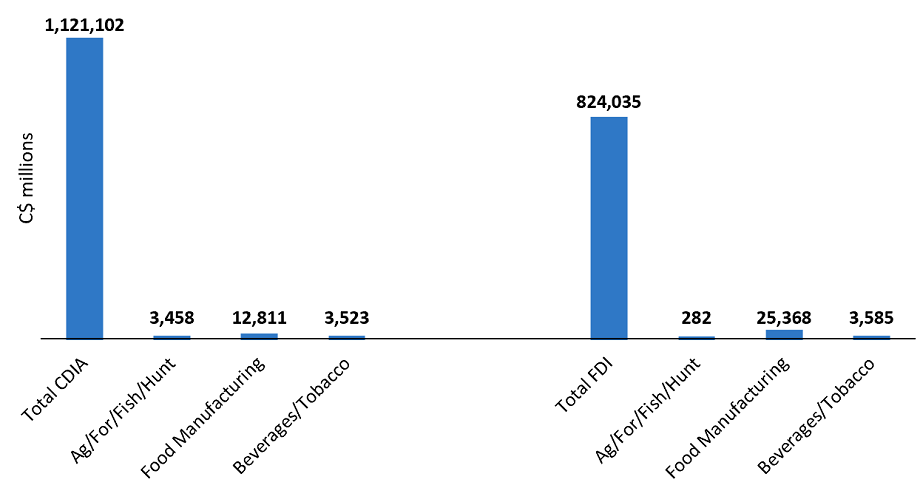

One of the most striking facts about the Canadian “agri-business” sector is the relatively low level of investment linked to international markets, both inward (into Canada, or FDI) and outward (Canadian direct investment abroad, or CDIA). The “stock” or book value of total agri-business investment (in and out of Canada) approximates $50 billion, as compared with nearly $2 trillion in CDIA and FDI (Figure 9). Therefore, the agri-business investment footprint is about 2.5% of total, a relatively small share.

CDIA increased at more than a 6% CAGR from 2008 to 2017 and totalled $1.1 trillion in 2017 (versus $642 billion in 2008). Of this, less than 2% of CDIA was in agri-business. This means that Canadian companies engaged in these activities are generally producing only in Canada and remain dependent on trade, rather than investing abroad where their presence would bring them closer to customers and position them to leverage supply chains and wholesalers in targeted markets.

All together, in 2017, such CDIA totalled $20 billion. The U.S. market was the main destination for primary agriculture ($3 billion) and food manufacturing ($7 billion), while Europe was the main destination for those investing in beverages and tobacco products ($3 billion). It remains to be seen if Canadian investors will increase their presence in European markets now that CETA is in force. Likewise, as exporters seek to diversify markets in the face of trade challenges with China, it remains to be seen if any Canadian investors will increase their presence in places, like Japan, Korea, and other CPTPP markets.

FDI increased at a nearly 5% CAGR from 2008 to 2017 and totalled $824 billion in 2017 (versus $551 billion in 2008). Of this, only 3.5% of FDI was in various agri-business categories, almost all food manufacturing.

In 2017, FDI “stock” or book values in agri-business totalled $29 billion, considerably more than CDIA levels, but still relatively small as a share of total FDI. European businesses were the largest investors, accounting for about $16 billion in investment, mostly food manufacturing ($14 billion) and beverages and tobacco products ($2 billion). As these figures were through 2017, it remains to be seen what impact CETA will have on future European investment into Canada. Following Europe is the U.S. ($10.5 billion), while other markets from the Americas and Asia have a small investment presence in the sector, mainly food manufacturing. This small presence is a contributing factor to why Canadian food processors are not more prominent in global supply chains and capturing more of a share of the higher value-added food and beverage markets around the world.

In addition to traditional exports, broadly referenced above (e.g., animal and plant products, processed foods), there are many non-traditional products and markets that offer opportunities to exporters for the future.

The organic sector is one bright light. An EDC Economic Insights paper Canada’s blooming organic food sector finds international buyers, published in February 2019, describes opportunities for Canadian producers and distributors in the organic products market. Some key findings from this research and how they relate to potential agricultural exports include:

Demand for organics in Canada is growing quickly at a rate of more than 15% annually. Domestic supply is having trouble keeping pace; in some cases, Canadian organic food processors are relying on imports, and are having difficulty finding reliable and consistent sources of ingredients. This is a call for increased investment in Canada, with potential slack to be considered for future export growth.

Additional research by EDC Economics based on data through 2015 highlighted opportunities in wheat and meslin, canola and colza, lentils and peas, lobster and scallops, cherries, and mushrooms. While these are captured in the higher-level trade statistics (mainly vegetable products), they’re highlighted because of the potential competitive advantages that Canada can harness to increase and diversify trade.

Wheat and meslin

Over the past several years, the global value of wheat and meslin exports has fluctuated, from a high of more than $44 billion in 2012 down to $34.5 billion in 2015. Canadian market share of exports has also ranged between 10% to 13%. In 2015, figures reached a 10-year high of 13.3%, worth nearly $5 billion. This is more than double values in 2006, constituting a 1.2 times’ increase.

Of even greater importance is the destination of wheat and meslin exports. While exports to the U.S. have traditionally been nearly double the second highest destination, 2015 marked a departure, pointing to trade diversification. (This may also reflect U.S. capacity to produce much of what Canada produces, as is also happening in China with canola.) Approximately 10% of wheat and meslin was exported to the U.S., 9% to Indonesia, 7% to Peru, and 5% to China. Of the Top 10 countries for wheat exports, all were emerging markets except the U.S. (first) and Japan (third). China, Indonesia, and Mexico, which have some of the highest annual rates of middle-class growth, feature in the Top 10. The figures bode well for future growth opportunities, although risks continue to loom. For instance, Italy has challenged Canadian durum wheat sales in that market on grounds of country-of-origin labelling on pasta products even after the introduction of CETA.

Canola and colza

Another valuable export commodity is canola and colza seed. Canadian share of the canola and colza export market reached a five-year high in 2015 at 43%, worth approximately $4 billion. The value of 2015 canola and colza seed exports was nearly five times values in 2006.

Export markets for these products are diverse and atypical when compared with standard Canadian trade patterns. Exports in 2015 were 42% to China, 21% to Japan, 14.5% to Mexico, and 7.5% to Pakistan.

Lentils and peas

Canada is the global leader in lentils and peas, both of which possess enormous potential as the value of plant proteins is increasingly integrated into personal diets around the world.

Canada’s share of the lentil export market reached a 10-year high of 73% in 2015, worth $2 billion. This represented a 33% increase from 2012. The 2015 value of lentil exports was more than eight times 2006 values. While Canada has long maintained about 65% of global lentil market share, the commodity’s recent popularity surge has resulted in significant dollar gains.

As for peas, Canada captured 51% of the dried and shelled pea export market in 2015, just below the 10-year average. In 2015, dried and shell pea exports totaled $970 million, above the 10-year average.

India has been the top destination for both pulses for years, accounting for 41% of lentil exports and 47% of pea exports in 2015. This presents a risk to Canadian exporters, as India introduced an import substitution policy in 2018 to stimulate greater domestic production of pulses.

Emerging markets ultimately account for a majority of the exports of both commodities, taking nine of the Top 10 spots for lentils (Spain was 10th) and eight of the Top 10 spots for peas (U.S. was fourth, and Japan was 10th). Like wheat and canola, lentils and peas show strong growth prospects. However, pulse exports will be heavily influenced by demand from India in the near term, which may mean an interim slowdown in global sales.

Lobster and scallops

Seafood exports account for more than 10% of total agri-food exports. Key existing and potential performers in this category include lobster and scallops.

The Canadian share of the (non-rock) lobster export market reached a 10-year high in 2015 at 46%. The global value of lobster exports has increased annually for the last decade as the Chinese and other emerging market middle-classes grow. The market reached nearly $1.5 billion in 2015.

Canada’s share of the market that year was nearly $675 million, or about 45% of global export sales. Although a large majority of lobster is exported to the U.S., exports to China (second-largest destination) exceeded 12%. More broadly, Canadian lobster is also being exported to a mix of developed (Belgium, U.K., Japan, South Korea) and emerging (Vietnam) markets. Increased sales in Asia, combined with the signing of CETA. suggest there will be opportunities for Canadian exporters to diversify markets.

There’s also long-term potential for scallops, another niche seafood product. Canadian share of global scallop exports increased nearly threefold from the mid-2000s to 2015, reaching 27% in 2015. Canadian scallop exports were worth $68 million in 2015, the second-highest figure in 10 years.

In this case, there’s very little trade diversification. Nearly all volume (99.5%) of Canadian scallops is destined for the U.S. market. It remains to be seen if there is import demand in other markets to diversify Canadian export markets.

Cherries have high growth potential. While market share is relatively small, compared to 2008 figures, Canada tripled its market share from 1.5% (2008) to 4.4% (2015). Export value in 2015 was $71 million, a 3.4 times’ increase from 2006 values.

Of the Top 10 markets for Canadian cherry exports, eight are located in Asia, while the U.S. is by far the largest market. Exports to the U.S. (57%) accounted for most sales. After that, China accounted for 21% of 2015 totals. High growth markets include Thailand and Vietnam.

Mushrooms

The value of Canadian mushroom exports, including truffles and those of the genus agaricus, was $141 million in 2015. Canada’s share of the global market reached 9% in 2015 as compared with 6% in 2006.

The percentage increase in market share understates the increase in dollar value. As Canadian market share has increased, so have global sales. The export value of mushrooms and truffles increased nearly 38% from 2006 to 2015 to more than $1.5 billion.

As with Canadian scallop exports, 99.5% of Canadian mushroom exports are destined for the U.S. market. Future growth is expected to occur in Europe and Asia, particularly with CETA in force and trans-Pacific trade likely to increase via the CPTPP.

Figure 1: Canadian agricultural exports, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 2: Canadian agricultural export shares by product, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 3: Canadian agricultural exports and total exports, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 4: Canadian agricultural imports, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 5: Canadian agricultural import shares by product, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 6: Canadian agricultural imports and total imports, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 7: Canadian agri-trade balance: agricultural exports less imports, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 8: Share of Canadian trade balance: agricultural exports less imports, 2008 to 2017

Source: Trade Data Online, EDC calculations

Figure 9: Share of Agri-business CDIA and FDI, 2017

Source: Statistics Canada, EDC calculations

https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/tdo-dcd.nsf/eng/home

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/type/data

Pulse industry worries about precedent as India slaps 60% tariff on chickpeas https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/india-chickpea-tariff-pulse-industry-1.4559947

Feds talk durum during EU trade mission https://www.producer.com/2018/10/feds-talk-durum-during-eu-trade-mission/

Pulse School: What do India's tariffs mean for pulse markets in 2018? https://www.realagriculture.com/2018/01/pulse-school-what-do-indias-tariffs-mean-for-pulse-markets-in-2018/

1Trade data are mainly sourced from Trade Data Online and cover 2008-2017. “Exports” include “domestic exports” as well as “re-exports.” Investment data are sourced from Statistics Canada. References are also made to agri-export estimates in 2018 (prior to when official data were made available) and the EDC forecast for 2019. All dollars are Canadian dollars unless otherwise specified.

2“Agri-business” includes agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and would generally correspond to the first three categories used in the trade data (i.e., live animals and animal products, vegetable products, oils and fats). Agri-business also includes food manufacturing and beverage and tobacco product manufacturing, both of which would correspond to the fourth category used in the trade data (i.e., food products, beverages and tobacco products). While the trade data did not include forestry, these data are not so large as to materially distort the general comparability of the aggregated figures. Data from Statistics Canada indicate that CDIA and FDI “stock” (book value) positions are low as a share of total in most agri-business categories, and that trends are negative in some cases. By contrast, CDIA and FDI have both shown growth since 2008, particularly CDIA.

Economic Insights is a publication series of concise reports written by EDC Economics staff on timely issues of relevance for Canadian international trade and investment. The views expressed in this report are those of the author and should not be attributed to Export Development Canada or its Board of Directors. This paper was written by Michael Borish; reviewed by Stephen Tapp.

For questions or comments, please contact Stephen Tapp. STapp@edc.ca

For media inquiries, please contact Shelley Maclean. SMaclean@edc.ca

Legal Disclaimer

These reports are a compilation of publicly available information and are not intended to provide specific advice and should not be relied on as such. No action or decisions should be taken without independent research and professional advice. While EDC makes reasonable efforts to ensure the information contained in these reports is accurate at the time of publication, EDC does not represent or warrant the accurateness, timeliness or completeness of the information. EDC is not liable for any loss or damage caused by, or resulting from, any errors or omissions.