MyEDC account

Manage your finance and insurance services. Get access to export tools and expert insights.

Solutions

By product

By product

By product

By product

Insurance

Get short-term coverage for occasional exports

Maintain ongoing coverage for active exporters

Learn how credit insurance safeguards your business and opens doors to new markets.

See how portfolio credit insurance helped this Canadian innovator expand.

Guarantees

Increase borrowing power for exports

Free up cash tied to contracts

Protect profits from exchange risk

Unlock more working capital

Find out how access to working capital fueled their expansion.

Loans

Secure a loan for global expansion

Get financing for international customers

Access funding for capital-intensive projects

Find out how direct lending helped this snack brand go global.

Learn how a Canadian tech firm turns sustainability into global opportunity.

Investments

Get equity capital for strategic growth

Explore how GoBolt built a greener logistics network across borders.

By industry

Featured

See how Canadian cleantech firms are advancing global sustainability goals.

Build relationships with global buyers to help grow your international business.

Resources

Popular topics

Explore strategies to enter new markets

Understand trade tariffs and how to manage their impact

Learn ways to protect your business from uncertainty

Build stronger supply chains for reliable operation

Access tools and insights for agri-food exporters

Find market intelligence for mining and metals exporters

Get insights to drive sustainable innovation

Explore resources for infrastructure growth

Export stage

Discover practical tools for first-time exporters

Unlock strategies to manage risk and boost growth

Leverage insights and connections to scale worldwide

Learn how pricing strategies help you enter new markets, manage risk and attract customers.

Get expert insights and the latest economic trends to help guide your export strategy.

Trade intelligence

Track trade trends in Indo-Pacific

Uncover European market opportunities

Access insights on U.S. trade

Browse countries and markets

Get expert analysis on markets and trends

Discover stories shaping global trade

See what’s ahead for the world economy

Monitor shifting global market risks

Read exporters’ perspectives on global trade

Knowledge centre

Get answers to your export questions

Research foreign companies before doing business

Find trusted freight forwarders

Gain export skills with online courses

Get insights and practical advice from leading experts

Listen to global trade stories

Learn how exporters are thriving worldwide

Explore export challenges and EDC solutions

Discover resources for smarter exporting

About

Discover our story

See how we help exporters

Explore the companies we serve

Learn about our commitment to ESG

Understand our governance framework

See the results of our commitments

MyEDC account

Manage your finance and insurance services. Get access to export tools and expert insights.

Economists and politicians have long advocated the need to diversify Canada’s international trade and investment to avoid overreliance on the U.S. market.

Even though the U.S. economy is performing well, and recent bilateral trade has been surprisingly strong, increased trade protectionism from President Trump has renewed the urgency for some Canadian companies to diversify their international business.

The federal government recently underscored the importance by appointing Jim Carr as the Minister of the newly-named International Trade Diversification portfolio.

In this blog, we analyze historical Canadian trade data and EDC surveys to uncover longer-term and emerging diversification trends.

So far this century, traditional merchandise trade data show a two-speed growth pattern. While Canada’s overall exports grew at 1.5% annually on average between 2000 and 2017, underlying growth with the U.S. was fairly weak at only 0.8%. Growth with the rest of the world was much stronger at 4.1%.

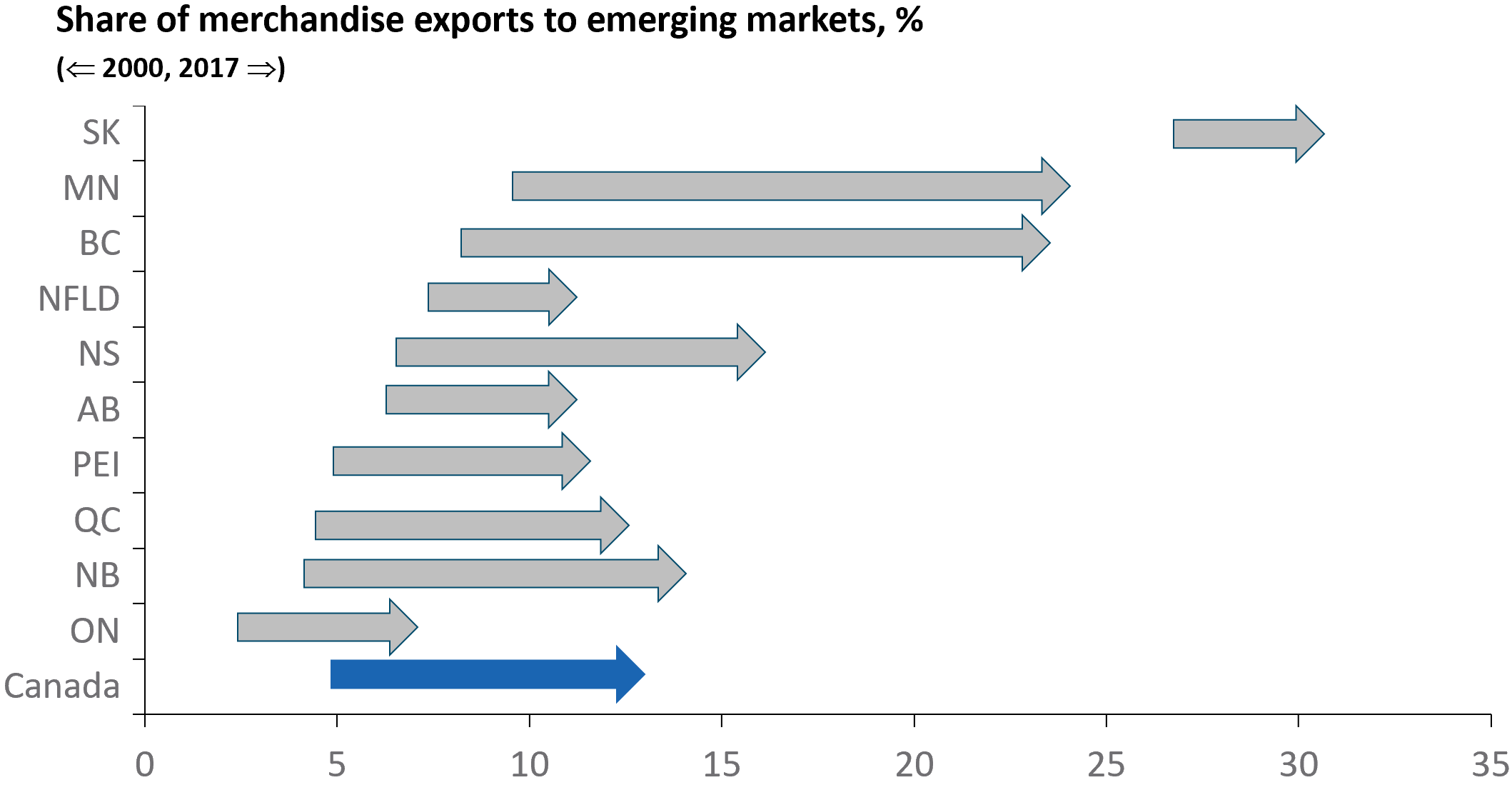

If we narrow the “rest of the world” segment down to emerging markets—which feature the fastest-growing countries such as China and India—the share of Canada’s exports to these destinations grew from 5% of the total to 13% over this period. This diversification has been remarkably broad-based. It occurred in all 10 provinces (see figure). Note that the most diversified provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and British Columbia are all in Western Canada.

Sources: EDC Economics; Statistics Canada

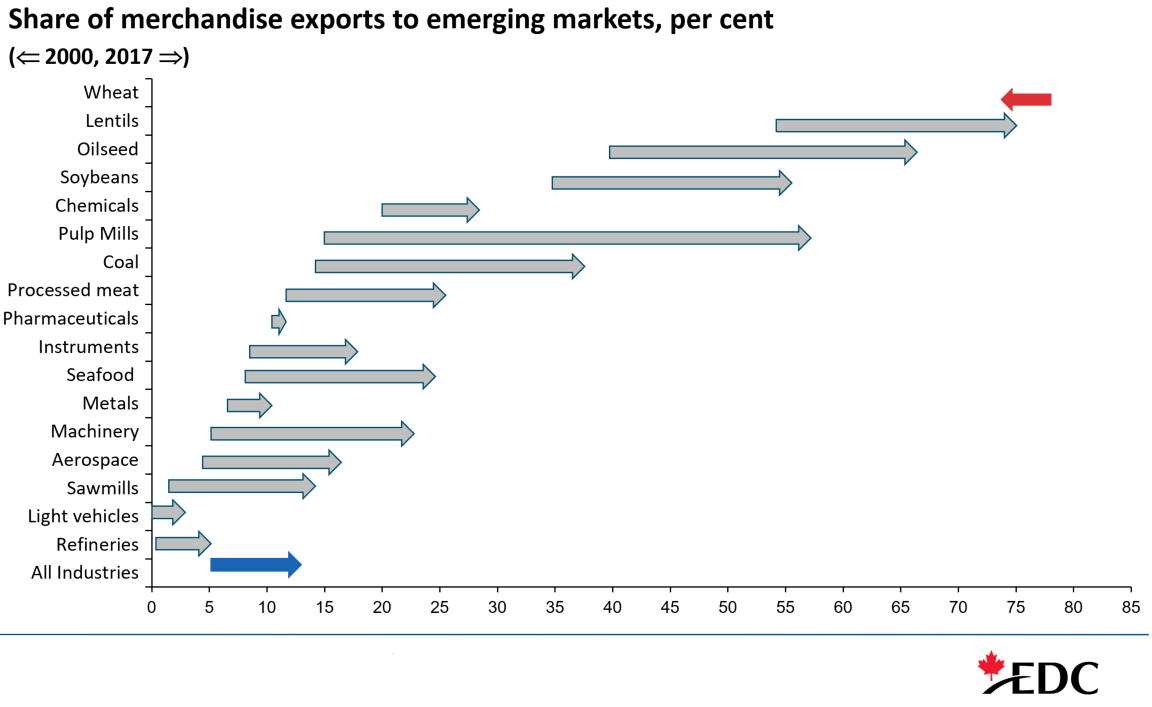

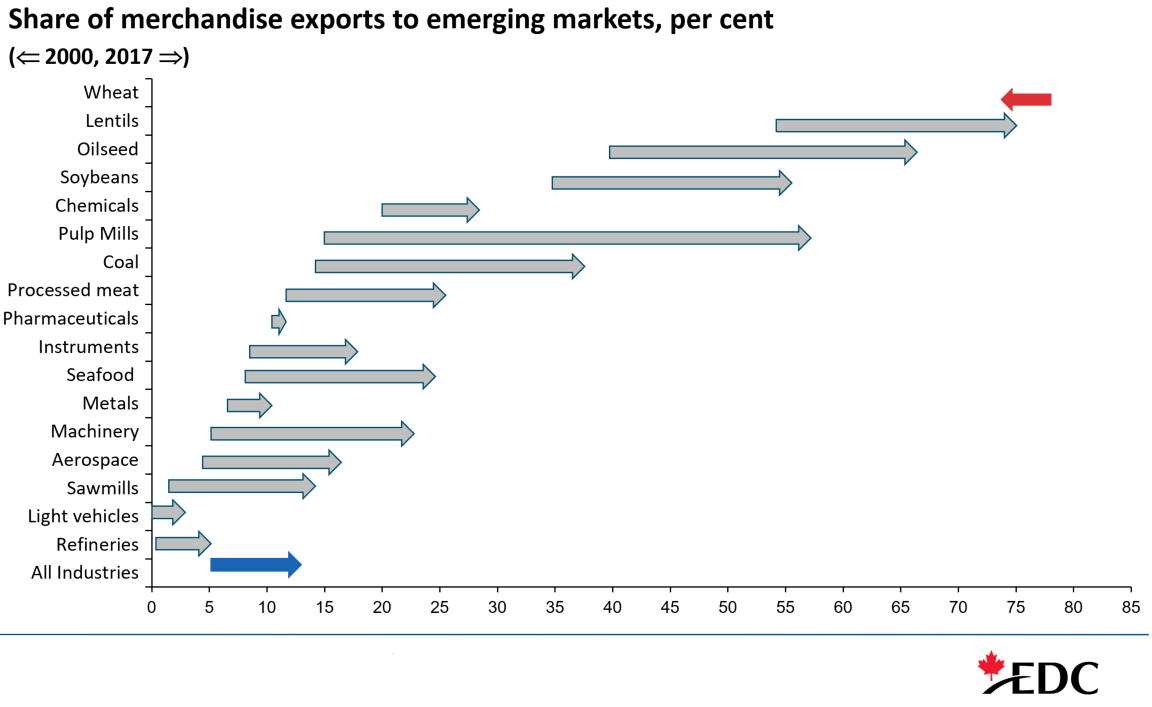

Diversification also occurred for 24 of 25 product categories (many of which are shown in the figure). The largest diversification gains occurred for paper products, coal, iron, soybean, oilseed and lentils; the only exception is wheat, which continues to have one of the highest shares destined for emerging markets.

Sources: EDC Economics; Statistics Canada

The U.S. versus non-U.S. difference is reflected in shifts in how Canada’s trade is transported. The majority of Canada’s trade with the U.S. takes place by road and, to a lesser extent, rail. Not surprisingly given the weaker Canada-U.S. trade performance, the shares of these transportation modes have collectively fallen over time (from 70 to 60%).

Conversely, Canada’s trade with other markets, such as Europe and Asia, primarily uses marine and air modes. These shares have increased, up from almost one-quarter to one-third (24 to 31%, respectively; the residual category is largely pipelines, which has increased from 6 to 9% of the total. These results show that Canada’s merchandise trade has become more diversified over time.

But how do we compare with other OECD countries?

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is a common way to evaluate a country’s export market concentration. Concentration is the opposite of diversification: a higher index closer to 1 indicates that a country’s exports are more concentrated, while a lower index closer to zero signifies more diversified exports.

First, the good news: since 2000, Canada’s exports have diversified more than the average OECD country. However, the bad news is that we remain the least diversified among the G7 countries and the second-least diversified among the 35 OECD countries. In fact, the two NAFTA periphery economies stand out in the figure, and only Mexico has more concentrated exports. In both cases, having the world’s largest economy next door and the highly-integrated continental supply chains built up under the North American Free Trade Agreement have exerted a strong gravitational pull—a pull that should endure, even if it is weakened.

Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, OECD countries, 2015

Sources: EDC Economics; World Bank

We’ve examined goods trade, now let’s consider other forms of commerce, before turning to the future.

Most trade discussions start with Canada’s goods exports, as we did above. However, expanding the scope shows that Canada’s international trade in services depends less on the U.S. market than our goods exports. This story is similar for both inward and outward foreign direct investment, where less than half of the total activity now involves the U.S. market. Notice that for all these measures, the share of Canada’s total international commerce occurring with countries other than the U.S. has grown over time.

Sources: EDC Economics; Statistics Canada

Looking ahead, one of the clearest findings from EDC’s recent Trade Confidence Index survey of 1,000 Canadian exporters is that, over the past six months, more Canadian companies have diversified their operations and are looking to do so in the future.

There was a significant increase in the share of Canadian exporters who have started exporting to new countries (44%, up from 31%, with increased international demand from a growing global economy being a main driver) and those who plan to export to new countries in the next two years (64%, up from 49%).

Source: EDC’s Trade Confidence Index

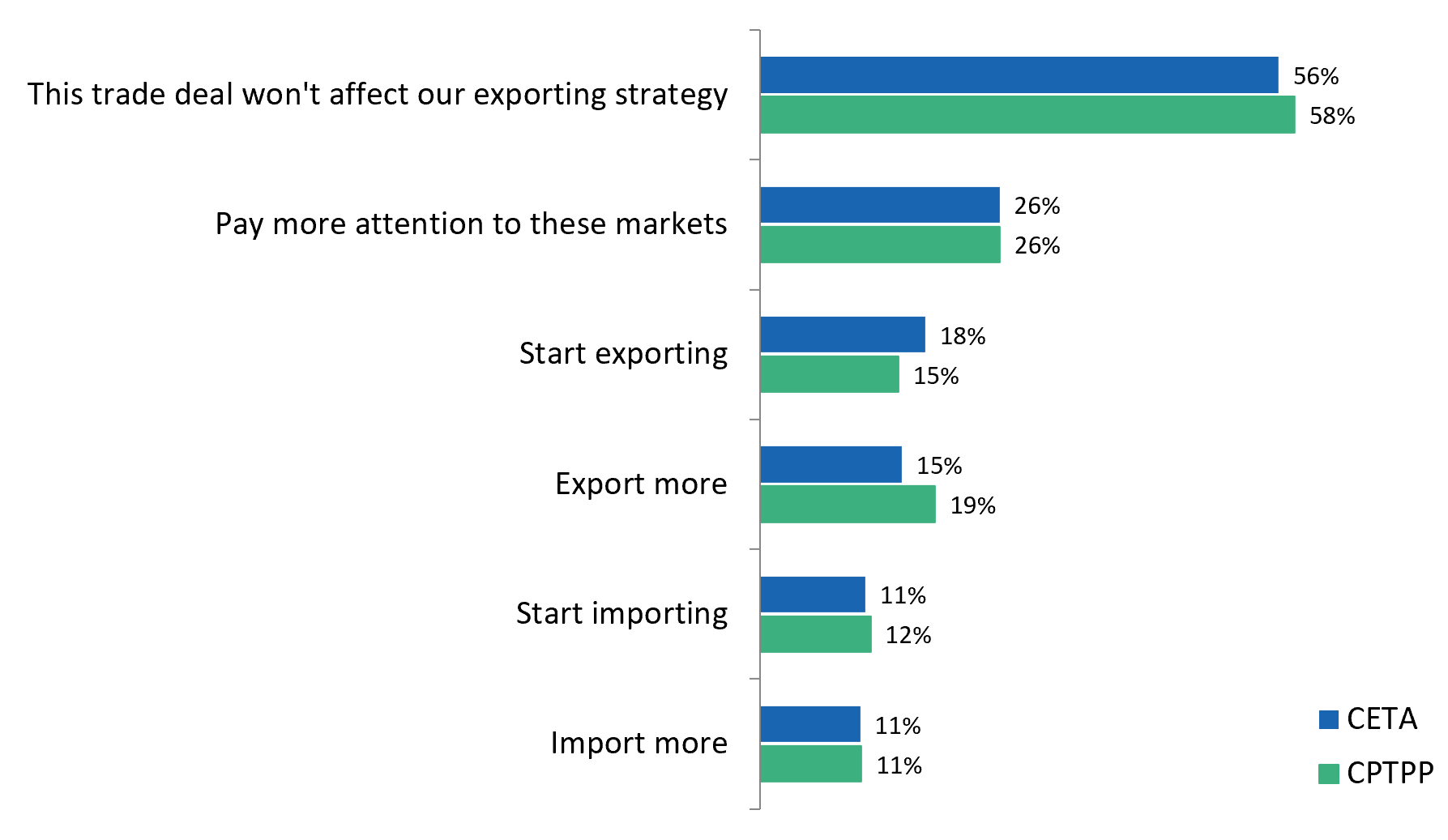

Canada recently signed two major trade deals with countries in the European Union and Asia Pacific region (namely the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, CETA, and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, CPTPP). Just over one-quarter of Canadian exporters say they are now paying more attention to these markets, particularly Germany, France and Japan. Existing traders in these markets are looking to increase exports and imports, and many Canadian companies are looking to start exporting to, and importing from, these trade blocs.

Source: EDC’s Trade Confidence Index

Beyond export market diversification, there was also a significant increase in the share of Canadian exporters who report having investments outside of Canada (17%, from 11%), and those who plan to do so (22%, up from 12%), where for the latter the U.S. and China are key target markets for planned Canadian foreign direct investments. These trends have already begun, as shown by the robust growth in Canada’s outward foreign direct investments in recent years.

In the new context of increased U.S. protectionism, it’s important to take a longer-term perspective, which reveals that Canadian commerce has been slowly but steadily diversifying away from the U.S. in recent decades. We expect this trend to continue as more Canadian exporters and investors increase their efforts to diversify their global operations. For the time being, it looks like many Canadian companies are viewing increased U.S. protectionism as a wake-up call and are responding by focusing on expanding to new markets.

Countries that share free trade agreements (FTAs) with Canada often make ideal new markets. Learn the basics of FTAs and how they can benefit your business.

Learn about key sectors, market trends, and how EDC supports Canadian businesses expanding to Europe.

An EDC economist helps you understand the different country risks at play.

With EDC’s support, this chemical analysis and measurement company has taken on international contracts from all over the world.

See how the heavily integrated supply chain between the Canada-U.S. automotive industries benefit both sides of the border.

“Keep calm and trade on” appears to be the motto for these Canadian companies, as they reveal their strategies for dealing in the U.S. market.