Brain surgeons and airline pilots have much in common. Both do their jobs better if they can simulate an operation or a flight in advance. And both need maps to guide them as well as systems to warn them of trouble ahead and to track their every move.

Simulators, flight plans, radar and black boxes have long fulfilled those functions for pilots. Neurosurgeons now have similar capabilities thanks to the imaging and robotic positioning technology developed by Synaptive Medical of Toronto.

Synaptive’s software brings together the various complex stages of brain surgery that up to now have been fragmented in separate procedures with little connection between them.

Although most of Synaptive’s 250 employees work in Canada, all its revenues have so far come from exports. In the two years since its first sale, Synaptive has sold its technology to leading hospitals in Buffalo, Denver, Detroit, Fairfax (Virginia) and Milwaukee, among others.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration cleared the system in April 2015 for use in U.S. operating rooms. But Jim Cloar, Synaptive’s chief commercial officer, says that complex regulatory requirements, which often vary from country to country, remain a key challenge.

In the case of the U.S., Synaptive followed what is known as a 510(k) pathway for gaining FDA approval. Section 510(k) of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act requires device manufacturers who must register, to notify FDA of their intent to market a medical device at least 90 days in advance. This allows FDA to determine whether the device is equivalent to a device already placed into one of the three classification categories.

Cloar says that many of the agency’s reviewers had doctorates in biomedical engineering and related fields, so that discussions were often highly scientific.

He advises anyone pursuing FDA approval to ensure that “everyone in the company, including investors, understand that the review does not happen in 90 calendar days. Any time the FDA asks for clarification, the review clock is paused. The clock resumes only when the agency receives a response from the applicant.”

Cloar adds: “Another valuable lesson is to have open and honest discussion with the reviewers so that they fully understand the intent of the application. Engaging engineers in discussions with the FDA and ensuring that the regulatory team is sufficiently knowledgeable in the technical aspects of the device is extremely important to expedite the review process.”

Synaptive pursued approvals from the FDA ahead of Health Canada because, in Cloar’s words, “we were lucky to have an immediate market in the US.” Further, he adds, Health Canada often does not stick to its published timelines for reviews, although it is moving in the right direction.

“The medical device industry very much welcomes any effort by Health Canada to grow its licensing team to support the large volume of applications,” says Cloar.

Synaptive recently made its first sale outside North America with the installation of an imaging and surgical navigation system in the Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan.

“We have seen extensive interest internationally and are in the process of obtaining regulatory approvals in various markets,” Cloar says. “We are hopeful that we will be cleared by Health Canada in the near future.”

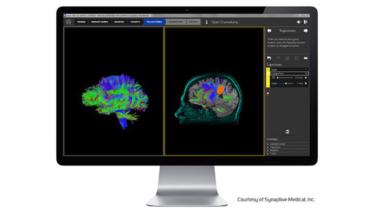

Synaptive’s BrightMatter technology has the potential to benefit hundreds of thousands of patients around the world with brain abnormalities that, up to now, were beyond a surgeon’s reach.

It enables surgeons to plan the best and safest route into the brain before the operation. This was previously a laborious, time-consuming process relegated largely to the radiology department.

During the operation, a detailed 3D image of the plan is visible on a large monitor, allowing the surgeon to minimize the potential for harm. This work can be done through an opening the size of a dime.

And when the procedure is over, surgeons and hospital administrators have a secure record of the entire procedure — how long it took, the costs, and the images. Such collaborative efforts, Cloar says, can help predict the outcomes of future operations, based on what’s been done in the past.

Synaptive’s sales rocketed from $1 million in 2014 to more than $10 million last year, with another big increase likely in 2016.

Most of the company’s imaging scientists, neuro-scientists and software engineers are based in the MaRS Discovery District in downtown Toronto, which describes itself as an “urban innovation hub” that encourages cutting-edge entrepreneurs by giving them access to useful networks and capital.

The company is working with researchers in Chicago to better detect concussions and battlefield brain injuries, which often elude traditional brain scans. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the brain disease found in football players with a history of head injuries, can at present only be diagnosed after death.

The new imaging technology may also help detect strokes, tumours, and degenerative brain disorders like Parkinson’s.

“The real story of Synaptive is that the company didn’t start by selling technology. It saw a problem of limited access to information, and built a solution to fit it,” Cloar says. “Companies that specialize in diagnostic radiology don’t translate through to the operating room with information on optics, navigation and surgical ergonomics.”

“Bridging this gap is where we started. But our future is in understanding the problems that exist throughout the entire process, and finding solutions that will ultimately translate into a new standard of care.”

Synaptive is confident that message will resonate not only close to home, but in hospitals around the world.

Get more exporting insights from Synpative Medical’s Jim Cloar here.