Solving the digital skills puzzle in the ICT sector

This article is the first in a three-part series that looks at the ICT sector, how it affects the Canadian economy, and how it impacts government policy and ultimately your business. Find out about the factors that contribute to our national digital skills deficit.

In this article:

Social. Mobile. Applications. Analytics. The cloud. The Internet of Things. Those aren’t just merely six buzzwords but rather the catalysts fuelling the digital disruption of the global and Canadian economies, being dubbed Industry 4.0.

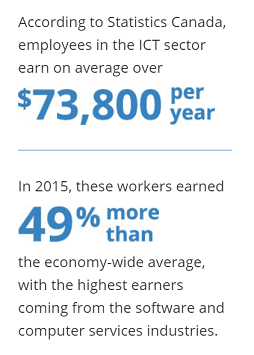

At the forefront of this digital revolution is Canada’s annual $72-billion Information Communications Technology (ICT) sector that is weathering the brunt of the growing pains. The challenge of change is never more evident than when you look at the demand for skilled talent in the industry.

According to the Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC), the continued growth of Canada’s digital economy will result in 182,000 new jobs by 2019. That number increases to 216,000—the population of Regina—by 2021.

Unfortunately, the domestic supply of ICT graduates and workers won’t be sufficient to meet demands. But it’s not solely a Canadian phenomenon; rather a global challenge, according to Jeremy Depow, Vice-President of Policy and Research at ICTC.

“This is not at all unique to Canada. Every country, regardless of size or economic standing, is facing a digital skills challenge,” he says. “Canada is immersed in a global race for talent.”

According the to the European Commission, there will be 825,000 new ICT positions by 2020 and in the U.S., it’s estimated that the demand for workers will reach 1.4 million in the same timeframe. It’s expected that only one-third of those American-based positions will be filled.

Canada produces approximately 29,000 new tech workers per year, but needs to graduate around 43,000 to keep up with demand.

“Globally, talent—or lack thereof—is the single biggest issue standing in the way of Chief Information Officers achieving their objectives in today’s digital economy,” states a December 2016 report by the Information Technology Association of Canada (ITAC). “Unfortunately, talent management practices aren’t keeping up with the ever-increasing and changing needs of the digital world.”

And not keeping up to the pace of change has broader business implications.

“This is more than just a hiring crunch. Unable to find the requisite talent, many Canadian companies (especially small- and medium-sized ones) are already unable to fill critical IT positions and they are falling behind in implementing new technologies as a result,” blogs Liz Wiebe from BC’s Groundswell Cloud Solutions.

“Canada stands to lose billions in productivity and tax revenues, to say nothing of its ability to innovate or maintain a competitive edge in a digital economy moving at fibre optic speed.”

That fibre-optic speed of technological change is the driving force behind the industry’s global skills crunch.

This is being fueled, in large part, by the rapid growth of the tech sector and the disruption it has on other sectors of the economy, which is very profound,

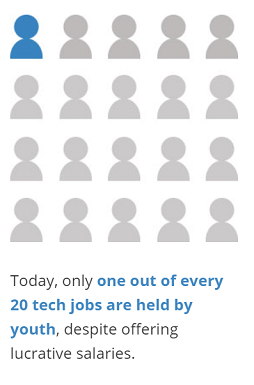

It’s also exacerbated by some fundamental issues, namely how the nation’s youth have historically not opted for a career in technology.

"Finding talent is a major challenge for the IT industry,” admits EDC’s Senior Associate covering the ICT sector, Megan Malone. “There are so many opportunities in this ever-evolving industry, but students are largely still not enrolling in IT programs. It’s likely that they are not aware that this is the direction the world is – and most industries are – heading, and the resulting demand that continues to grow so rapidly for IT experts. The reality is that if you have an IT background, you likely won’t have much issue in finding a job."

However, the message that the sector boasts high-paying career opportunities may be sinking in. According to Cutean, post-secondary enrolment numbers in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) or ICT have increased by nearly 25 per cent since 2010. Nevertheless, those numbers aren’t high enough to ensure domestic demand is met by graduating students alone.

Compounding the issue are the worker demographics in the ICT sector. The majority of the workforce is between 25 to 54 years of age and there’s a looming wave of “baby boomer” worker retirements on the horizon. The sector’s gender gap is a major challenge as well with female ICT workers accounting for only 24 per cent of the total workforce.

The “brain drain” issue that was so prevalent in Canada before the tech crash in the early 2000s, is making a resurgence.

“There are many innovative start-up companies in Canada that have been and continue to be born out of legacy companies like Nortel,” says EDC’s Malone. “But the trend is that many get acquired early on, usually by larger U.S. companies and the talent goes with them. One of the biggest challenges is retaining that talent in Canada, especially at the executive level.”

While the statistics paint a daunting picture, there’s an opportunity for Canada to become a leader in solving the global talent challenge. With a foundation of a strong digital ecosystem, low unemployment and high demand in many sectors of the digital economy, the nation is well positioned for success, but needs to take action.

“Canada has the means to become a global leader in the digital economy, but we must boldly tackle the skills challenge—the industry’s number one priority,” says Depow. “However, there’s absolutely no silver bullet that will solve this.”

That’s why any solution will require a holistic approach. Domestically, it must focus on attracting youth, encouraging more women as well as engaging Canada’s indigenous population.

Immigration is also a critical piece in Canada’s skills shortage puzzle.

“We won’t be able to fill 216,000 positions unless we look around the globe and attract the best and the brightest,” Depow adds. “We need to ensure that companies don’t have huge regulatory immigration barriers to bring people into Canada quickly.”

Cutean says that the benefits of acquiring global talent through immigration go beyond the skills crunch.

“It will create new job opportunities, as well as enrich the sector and the country as a whole,” she adds.

Focusing on a more comprehensive STEM-based curriculum beginning, from Kindergarten to Grade 12, is necessary to foster tomorrow’s innovators with much-needed digital skills. Historically, the interest in STEM-based courses wanes by the time students reach secondary school.

That’s why integrated learning is crucial.

“We can’t underestimate the value of work-integrated learning,” Cutean says.

“Students might learn that a bachelor degree may not necessarily be completely relevant to the market when they graduate (due to technological change), but [work integrated learning] gives the students the opportunity to practice their skills while they study. This experience will help them hit the ground running once they start a job.”

The federal government’s 2017 budget, dubbed the “Innovation Budget,” was a much-needed piece to the puzzle, says Depow.

“It provided the needed leadership on innovation,” he says.

Key highlights in federal budget include:

- Investing $50 million over two years to enhance youth skills including initiatives aimed at teaching kids to code, investing in organizations that support STEM development in children and promoting advanced digital literacy

- Increasing opportunities for youth to obtain skills and gain work experience through an expanded Youth Employment Strategy and the Work-Integrated Learning program

- Invest in retraining and adult skills development, with the aim of creating easy access skill development and digital literacy

- Allocating $275 million to fund a new organization to identify skills gaps, explore innovative methods of skills development and develop metrics to guide investments.

- Earmarking $7.8 million for Canada’s Global Skills Strategy

However, government alone won’t solve the skills challenge. It’s time for industry, academia and governments across Canada to align and act, Depow says.

“What’s truly missing right now is leadership and alignment,” he adds. “We need to develop a national body to bring all the pieces together. Digital touches all sectors and has benefits for all Canadians.”

And time is of the essence.

“Right now, as a country, we have a choice to make. Do we want to piggyback on what other countries are doing, wait and see what technologies emerge or do we want to lead? Are we going to give up the opportunity or are we going to get bold, act and position Canada as a leader?” Depow says. “We don’t have 25 years to figure this out. We have maybe three, then we will be left behind.”