Globalization’s future: Disrupted, not defeated

Author Details

Ross Prusakowski

Deputy chief economist

In this article:

In the past decade, the global economy has faced numerous challenges, leading many to claim that the era of globalization is ending. After decades of driving economic growth, innovation and investment flows—and helping millions escape poverty—some believe this megatrend has met its match. Tariffs, trade wars, geopolitical fragmentation and the pandemic’s shock and recovery are widely presumed to have defeated globalization.

But our assessment suggests otherwise.

These challenges are certainly disrupting and changing how globalization operates, but they aren’t enough to eliminate its incentives or influence. The forces driving connectivity—technology, communications and economic interdependence—make a complete reversal virtually impossible. What we’re witnessing isn’t the end of globalization, but its transformation.

Explore EDC’s latest Global Economic Outlook for global trade trends

With growing risks, Canadian companies face new challenges. EDC’s Global Economic Outlook offers insights to help you make better business decisions.

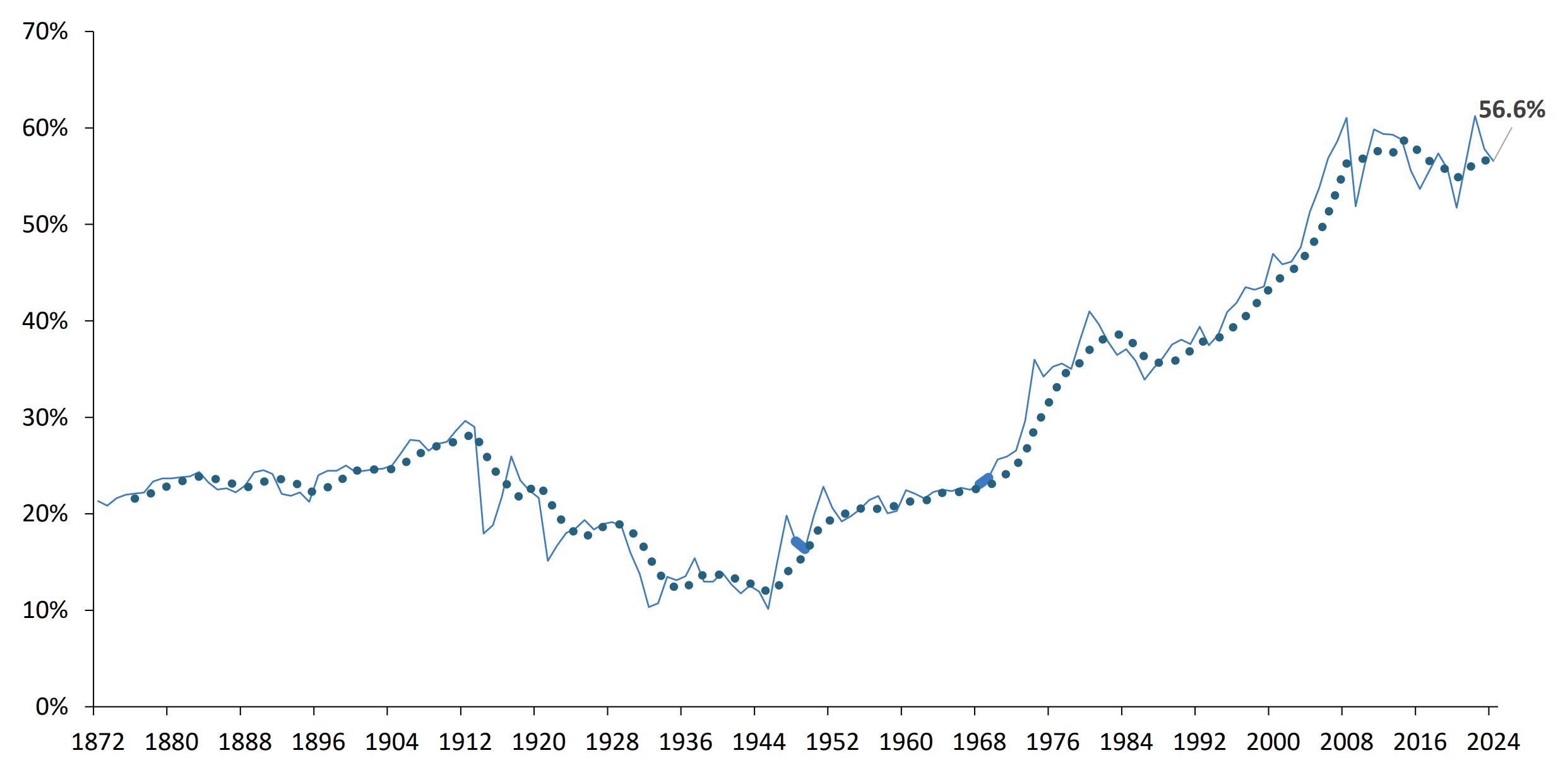

In international business, globalization describes the increasing connectedness and interdependence of world economies, making it easier to move goods and services across borders. There are many ways to discuss and consider globalization, but the main measure, in our view, is the evolution of trade as a share of global gross domestic product (GDP) (see Chart 1).

After more than 150 years of economic, technological and political developments, it’s clear that the global economy has become more interconnected. But progress hasn’t been seamless or linear.

World trade to GDP and five-year moving average (%, nominal)

Source: Klasing & Milionis 2014 (1871-1949), Penn World Table (1950-1969), World Bank(1970-2024).

The rapid growth of global trade and globalization in the early 2000s was driven by China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the internet’s impact on trade flows. That period saw almost unparalleled growth. But over the previous century, the share of trade in global GDP has ebbed and flowed. From 1912 through to the end of the Second World War, trade shrank due to war, the Great Depression and political fragmentation. After a period of expansion, trade again retreated in the early 1980s as interest rates and oil shocks triggered a modest pullback.

Since the global financial crisis in 2008, the share of global trade has been relatively stagnant. Initially, protectionist measures and trade policies increased worldwide as governments sought to protect key industries and constituencies during economic upheaval.

This trend continued through the first Trump administration and Brexit (the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union), which frayed long-standing trade relationships, and has accelerated since the new U.S. administration took office in early 2025. New U.S. tariffs and trade restrictions have prompted retaliatory actions from key trading partners, raising costs for businesses and disrupting supply chains. Two-thirds of global firms report tangible cost increases tied to trade policy uncertainty and duties.

The global pandemic further disrupted supply chains, causing costs to surge and inventories to run out, which intensified these trends. As a result, companies and governments have pursued strategies, like nearshoring, to build resilience in the face of uncertainty.

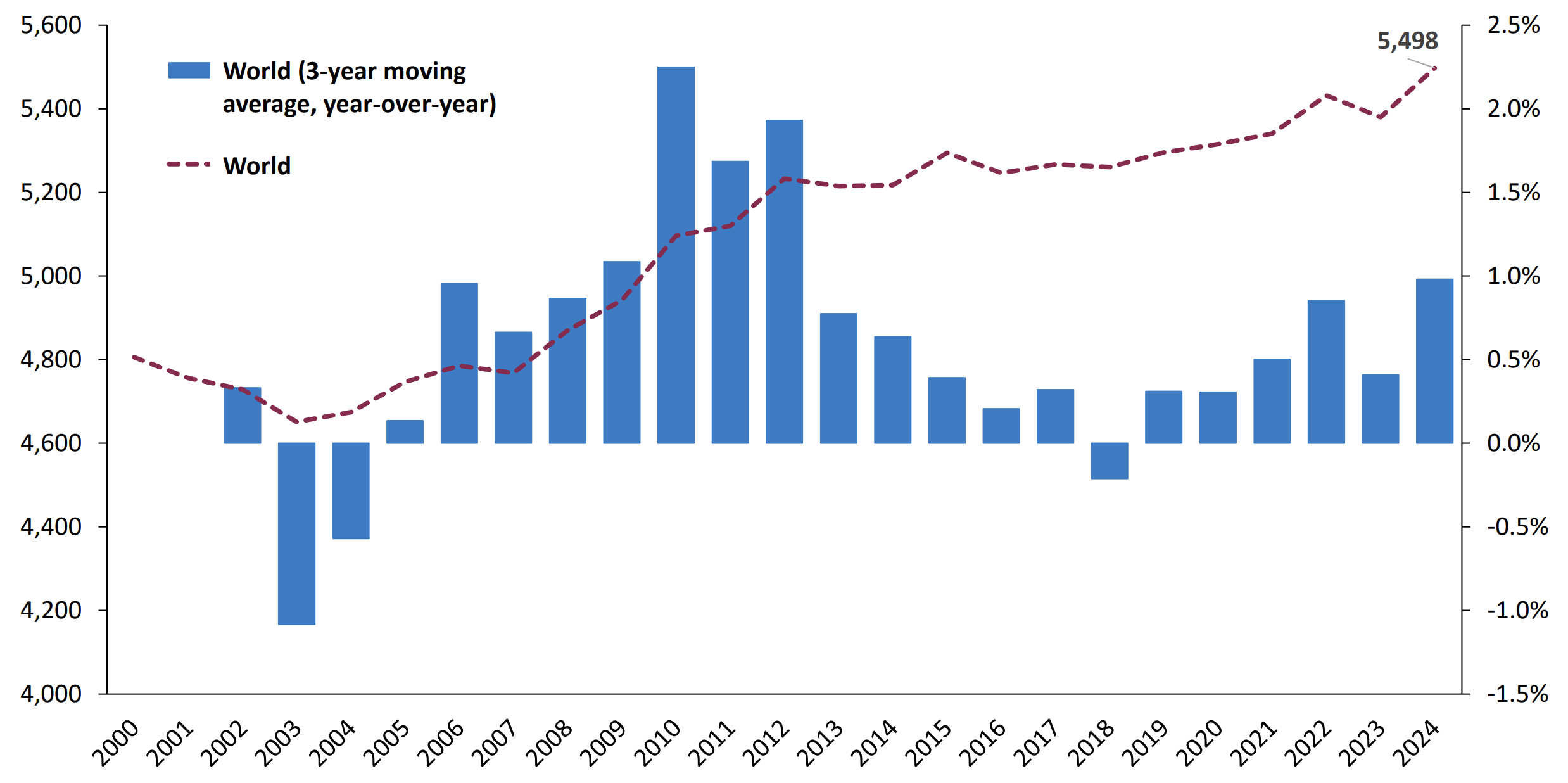

While the overall share of trade to global GDP is a key measure of globalization, other indicators can reveal how it’s changing. For example, the distance travelled by imported goods provides insight into the evolution of supply chains and global integration.

As Chart 2 shows, the trade-weighted average import distance has increased significantly since 2000. Although China joined the WTO in 2001, it took several years for the impact to echo through supply chains. Between 2003 and 2012, globalization accelerated as import distances increased rapidly. While China was a key player, other emerging economies—Vietnam, India, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Malaysia and others—also played important roles.

Global trade-weighted distance of imports (kilometres)

Source: World Trade Organization, Haver Analytics and EDC.

The distance travelled data supports the assessment that the pace of globalization has slowed in recent years. Although the distance travelled by imports has continued to increase—despite challenges and the reshaping of global supply chains—growth has slackened, compared to the first decade of the century. Despite supply chain pressures, globalization hasn’t reversed.

It's important to note that this data only covers goods trade and doesn’t capture services. In an era where technology and communications networks enable seamless global connections, this is a significant omission. The importance of services exports continues to grow and for advanced economies, like Canada, services are becoming an even more vital part of trade.

Limited global evidence suggests that globalization is boldly continuing in services exports, as cross-border financial services, educational offerings and increased global tourism persist. This analysis shows that globalization isn’t reversing. In our view, it would be difficult for almost any geopolitical headwind to truly unwind globalization because of three key structural factors:

- Technology and communication: Digital platforms, cloud computing and instant communications have made cross-border collaboration seamless. Businesses can co-ordinate production, marketing and logistics across continents in real time. This connectivity isn’t easily undone; even if physical trade slows, the exchange of ideas, services and data will continue to bind economies together.

- Economic interdependence: Global supply chains are deeply entrenched. From semiconductors to pharmaceuticals, production networks span multiple countries. Reshoring and “friend-shoring” may reduce some vulnerabilities, but dismantling these networks entirely would be prohibitively expensive and disruptive—something companies can’t easily undertake.

- Innovation and capacity building: Trade today isn’t just about goods—it’s about capabilities. Consider clean technologies, advanced manufacturing techniques and other advanced capabilities. The physical equipment itself relies on vast supply chains spanning countries and companies across the globe, while the underpinning software and research can rely on dozens—possibly hundreds—more people who are equally dispersed. The network effects of this work are too advanced and intertwined to be easily undone. Just as the development of a standardized shipping container supercharged global trade in the last century, online connections are doing it now.

While we don’t see an end to globalization, we expect that events and trade challenges will force it to evolve. To build strength while maintaining the benefits of diversified supply chains, companies will look toward regionalization in trade. Expansion within trade blocs such as the European Union (EU), Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries and Canada-United States-Mexico is likely.

The early part of the 21st century saw companies prioritize cost above all else. Today, resilience matters more. Firms are increasing and diversifying their supply chains—even at higher costs—to guard against shocks from tariffs, pandemics, or geopolitical challenges.

Globalization is under strain, but it isn’t unravelling. Tariffs and political tensions will reshape trade patterns, yet technology, communications and shared economic interests make a full retreat implausible. The future may mean a more fragmented, regionalized form of globalization—one that prioritizes resilience and sustainability over pure efficiency. For businesses and policy-makers, the challenge is clear: Adapt to this new reality without losing sight of the opportunities that global integration continues to offer.

In short, globalization is changing, but the world remains deeply connected—and that’s unlikely to change. As Chart 1 shows, there have been many challenges to trade and globalization across history, but the world continues to become more interdependent. Check out EDC’s Trade Confidence Index for exporter outlooks.